New York City News Service

Aging In Place

Graison Dangor, Janaki Chadha, Sarah Min, Shari Straker, Allie Weintraub, K. Dominic McKenzie, Sharif Paget, Laura Olivieri Robles

Hundreds of seniors gathered on the steps of city hall in early May. They were not rallying for a single cause. In the crowd, seniors held up signs demanding more support for senior centers, services for elderly LGBT people, and more accessible transportation.

Seniors, or those over age 60, are 13 percent of the city’s population– and growing. They face the same challenges as all New Yorkers — such as skyrocketing rent and unreliable, often inaccessible public transit — but have fewer means to adjust to the changes. Many live on fixed incomes, making it harder to adjust to increased costs of living, and have limited physical mobility, which puts most of the city’s public transit out of reach.

In this series, we have three stories highlighting how seniors from different walks of life are making a life in New York City.

THE COST OF AGING

Rising rents and other costs are making it tough for seniors on fixed incomes to stay in their longtime homes. See which neighborhoods have the most seniors living in poverty – and which have the fewest.

A PLACE TO CALL HOME

New York has long served as a refuge for LGBT people. But there are few LGBT-friendly housing and support services for seniors. See how the city is trying to change that.

AN UNFAMILIAR MENU

. The number of New York seniors born outside of the U.S. nearly matches the native-born elderly population. But diverse meal options are elusive at senior centers. See how some centers are working to serve culturally appropriate food.

The Cost of Aging

S H A R I F P A G E T , L A U R A M . O L I V I E R I R O B L E S & G R A I S O N D A N G O R

Angelica Thomches, 81, moved to Astoria, Queens, in 1967. She sold her house five years ago. The reason: The neighborhood got too expensive.

She now lives in Throggs Neck with her son’s family, but misses the place she called home for decades. “I love them, I’m happy with them, but it’s not the same,” Thomches said.

Thomches’ story is all too familiar: Elderly folks either leaving their longtime homes or struggling to make ends meet.

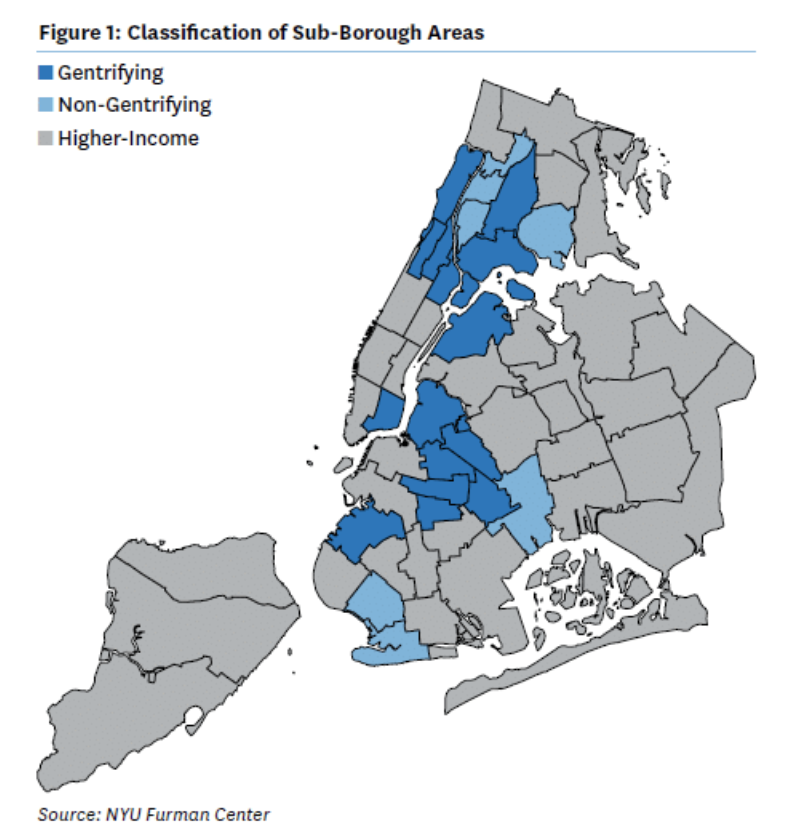

New York, one of the most expensive cities in the U.S., presents multiple challenges to those on a fixed income, living largely off Social Security. Basic necessities, such as housing and food, are becoming harder to afford as the costs soar. Areas like Greenpoint and Lower East Side, which traditionally drew low-income tenants, are now pricing out many longtime residents.

The problem becomes worse as the city’s population ages: Between 2005 and 2015, the number of people older than 65 increased by more than 19 percent, rising to 1.13 million, according the city Comptroller’s Office.

Seniors, meanwhile, are working longer or re-entering the labor market. The number of employed seniors grew by 62 percent between 2005 and 2015. Among the reasons: The large Baby Boomer population is shunning retirement, people are living longer and folks can’t afford to live on fixed incomes.

Many who aren’t working are struggling. In several city neighborhoods, the income of more than 35 percent of adults over 65 falls below the poverty line.

%

Number of Seniors "Rent-Burdened"

High poverty rates for seniors, not surprisingly, can be found in community districts with a low average income. But seniors in booming one-time working-class neighborhoods also are facing a financial crutch.

On the Lower East Side, where the average rent has increased by 50.3 percent since 1990, according to a report by NYU’s Furman Center for Real Estate and Urban Policy, the poverty rate is 37 percent. The poverty figure is 38 percent in Bushwick and 27 percent in Greenpoint, both areas where rents have jumped in recent years.

Overall, 60 percent of city seniors spend more than 30 percent of their income on rent, meaning they are “rent-burdened” under federal guidelines.

“In Chinatown, we are hearing of seniors doubling up some sleep with friends on couches,” said Katelyn Hosey, of LiveOn NY, an organization that advocates for seniors.

Hosey joined the crowd that gathered outside of City Hall in May to call for more funding for senior services in a city whose elderly population is expected to double by 2030.

a place to call home

A L L I E W E I N T R A U B & K . D O M I N I C M C K E N Z I E

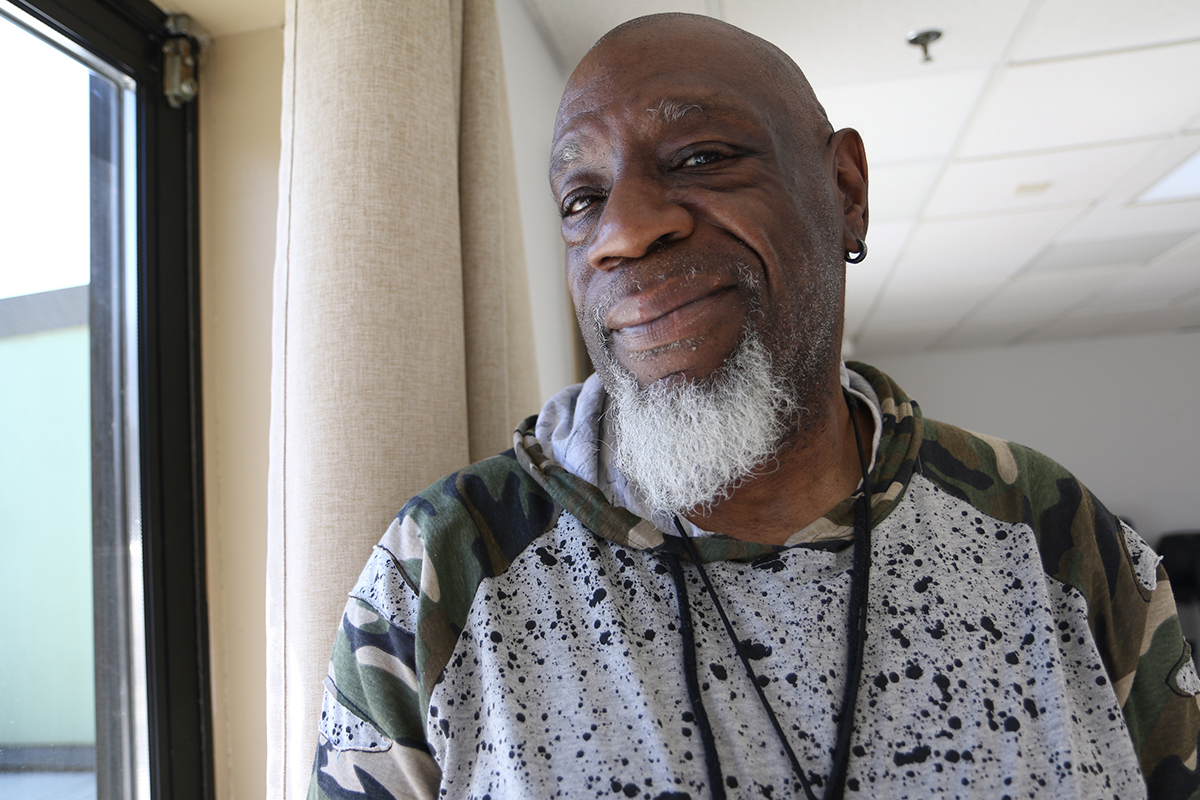

George Phipps is estranged from his family, whom, he said, does not know he is gay and living with HIV.

But as an aging New Yorker, he has found comfort in a building with others like him – and the medical services he needs to enjoy the latter years of his life.

“(My family) thinks I am dead…I came out in my 50s,” said Phipps, 58,

“It was one of my best friends here who helped me come out. ‘Cause he’d been through the same thing I’d been through. I’m thinking, growing up, nobody had ever been through it. ‘Cause I had never been around nobody who had been through that.”

Phipps is staying at the Keith D. Cylar House Residence & Health Center on the Lower East Side. The residence is run by Housing Works, a nonprofit that provides accommodations for people living with HIV.

Phipps is now in search of a comfortable place he can call his permanent home.

A recent AARP survey found that nearly three-quarters of LGBT seniors indicated they had at least one serious health condition. One in four reported a mental health issue or substance abuse disorder. More than 90 percent are interested in LGBT-friendly housing developments with in-house support for older adults.

New York is ranked as the 11th best city in the country for successful aging, yet there aren’t any public residences for LGBT seniors. As New York’s elderly population increases, those who identify as LGBT seek affordable housing with on-site health services.

“People who are stably housed, they have better health outcomes,” said Steve Hemraj, former chair of the HIV/AIDS Services Administration (HASA) advisory board. “If they have a place to live, they keep their doctors’ appointments, they can store their medication, they’re comfortable, they live happier lives.”

Services and Advocacy for GLBT Elders (SAGE) and HELP USA

have teamed with the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) to build two subsidized LGBT-friendly developments: the Crotona Senior Residences in the Bronx and Ingersoll Senior Residences in Brooklyn. The ground floor will house a SAGE Center, hosting computer classes, case managers and a resident nurse practitioner.

Construction began with a ground-breaking at the Crotona site in May. The developments are set to open in 2019.

“All New Yorkers deserve a safe, affordable home with the support and companionship that a robust community offers,” said New York State Commissioner of Homes and Community Renewal RuthAnne Visnauskas. “We are proud … to serve the needs of the aging LGBT community – and all seniors – here in the Bronx.”

Phipps hopes to get a spot in one of the new developments.

“When I move, the first thing I’m doing is cooking a turkey … I’m gonna cook and tell y’all to come over and eat,” he said. “My blood family won’t deal with me … my new family? I know they’re gonna be there for me.”

%

of LGBT seniors interested in LGBT-friendly housing in the U.S.

He is receiving Supplemental Security Income (SSI) and benefits from the HASA program administered by the city’s Human Resources Administration. Through that program, he, like many others living with HIV, are able to receive assistance with rental costs, transportation and other necessities. The city will pay 70 percent of rental costs, leaving the person to pay the remaining 30 percent.

This assistance can be used to rent a new apartment at one of these developments.

Construction began with a ground-breaking on the Crotona site last Thursday.

New York State Commissioner of Homes and Community Renewal RuthAnne Visnauskas was at the event and said the state is proud to be working alongside SAGE and HELP USA.

“All New Yorkers deserve a safe, affordable home with the support and companionship that a robust community offers,” she said. “We are proud … to serve the needs of the aging LGBT community – and all seniors – here in the Bronx.”

The developments are set to be opened in 2019.

On settling in a new home, Phipps is excited at the prospects.

“When I move, the first thing I’m doing is cooking a turkey … I’m gonna cook and tell y’all to come over and eat,” he said. “My blood family won’t deal with me … my new family? I know they’re gonna be there for me.”

BETWEEN KALE AND KIMCHI

S A R A H M I N , S H A R I S T R A K E R & J A N A K I C H A D H A

Even after living in the United States for 43 years, Han-Young Song finds it difficult and often embarrassing to order food in English at American restaurants. And he never likes the Western-style entrees.

Instead, the 77-year-old Song heads to the Korean Senior Center in Flushing, where he can purchase a Korean breakfast for 75 cents and lunch for $1.50.

Breakfast usually includes jook, or porridge, that ranges from savory (vegetables) to sweet (red bean). Lunch includes rice, kimchi, soup and meat.

“Even if it’s the same meat, it’s different,” Song said in Korean. “Here, beef has a Korean marinade. It’s Korean-style cooking. There, they just serve a thick cut of steak.”

In New York City, the senior population is increasingly ethnically and culturally diverse. But most senior centers are not providing culturally appropriate meals to meet the needs of the immigrant population.

“There’s definitely more demand than is being met now,” said City Council Member Margaret Chin, chair of the Council’s Committee on Aging.

More than 300 Korean seniors travel to the Korean Senior Center in Flushing to meet other Koreans, make new friends and play rounds of Go. On Fridays, the center offers seniors extra bagged lunches to take home for the weekends.

“Making sure that senior centers have culturally appropriate meals is crucial to making sure that senior centers are relevant to the multicultural senior population of today,” said Christian González-Rivera, senior researcher at the Center for an Urban Future.

“Because food brings people together, the kind of food a senior center serves speaks volumes about who and who is not welcome there,” she added.

The city’s Department for the Aging distributes Korean meals in Queens, Spanish food in the Bronx and Chinese meals in Lower Manhattan. Overall, the agency provided 7.2 million meals to seniors in its 250 senior centers in 2017.

Some DFTA administrators worry, however, about health risks from comfort foods that are rich in sodium.

In 2017, for the first time since the end of World War II, the number of elderly New Yorkers born outside the U.S. (49.5 percent), nearly matched the number of native-born seniors, according to a report from the Center for an Urban Future.

The senior immigrant population is also growing faster than the native-born elderly population, the report found. The number of immigrant seniors increased by 21 percent between 2010 and 2015, compared to a 6 percent hike in the population of native-born seniors. This trend was most prominent in Brooklyn: The foreign-born senior population rose 30 percent, while the native-born senior population fell 4 percent.

At the Christopher Blenman Senior Center, which caters to a predominantly Caribbean population in East Flatbush, Brooklyn, program director Merlyn Bruce manages the food orders for the kitchen. She ensures that the senior center serves culturally appropriate foods that are compliant with DFTA health standards.

“Most of our food, we don’t cook with salt… [we] enhance the food with the different spices, fresh thyme, oregano,” Bruce said.

The center serves meals with oxtail, peas and rice to the predominantly West Indian senior community. The facility hosts “culture days” where one country is recognized. In March, the seniors celebrated Jamaica.

“Our motto is come to the center and feel a home away from home,” Bruce said.